A 17th century bottle, made using the Mishima inlay technique.

In the second part of our A to Z of Japanese pottery, we provide a run-down of the main styles, from Mino ware through to Tamba Ware. Along the way, we offer plenty of pointers on how to recognize the differences between them all.

A Mino Setoguro blackwear tea bowl known as the “Iron Mallet.”

Pottery has been produced in the Mino area of Honshu island since at least the 7th Century, making it one of the oldest types of Japanese pottery. Although Mino Province no longer exists – the region is now a part of Gifu and Aichi Prefectures – its name lives on in the form of Minoyaki; pottery produced principally in the towns of Kani, Tajimi, Toki, and Mizunami.

Many of the earliest examples of Mino ware closely resemble Bizen ware. This fact has prompted some historians of Japanese pottery to suggest that the first Mino kilns were established by potters who relocated from the Bizen area.

As the pottery produced in this region has changed in style over the centuries, Mino ware can be considered something of an umbrella term encompassing several distinct genres. Indeed it’s said that there are as many as 15 distinct types of Mino ware. The main styles are Kiseto ware, which is a soft yellow due to its iron-rich glaze; Oribe ware, which is a deep shade of green; Setoguro ware, which is black and was mainly produced in the 16th Century; and Shino ware, which usually has a thick white glaze, often with red scorch marks. Some kilns also produce a version of Ofuke ware, despite this style having originated in Nagoya.

Beyond a shared geographical origin, what unites these disparate styles of Japanese pottery is that they are largely designed as utilitarian objects for everyday use. And the eclecticism of traditional Mino ware lives on in the diverse styles of tableware fired by local kilns today. Indeed, a very large percentage of contemporary pottery made in Japan still comes from the region.

A Mishima inlay tea bowl, made in Korea for the Japanese market.

As we’ve already seen, most styles of Japanese pottery get their names either from the geographical region in which they were made, or from the name of the individual or family credited with their invention. Mishima ware does neither.

To be clear, Mishima is the name of a place. Or rather, it’s the name of several places. But none are the clear home of Mishima pottery.

One theory is that Mishima ware acquired its name from a calendar published by the Mishima Taisha shrine in Mishima, Shizuoka prefecture, that incorporates a similar design to the incised lines on Mishima pottery. A style of decoration that was in fact first developed in Korea.

Another is that the name Mishima – which, depending on the kanji used to write it, can mean “three islands” – refers to a whole variety of different pottery imported from the islands of Taiwan, Luzon, and Macau. The only problem with this latter theory is that the kanji in the first recorded use of the term Mishima ware is not the same as the kanji for “three,” but instead means “to see.”

Meanwhile there is an Island off the coast of Yamaguchi – which lies in the direction of both Korea and the islands of Taiwan and Macau (and roughly Luzon) – that is also called Mishima, but this time using the kanji “to see”. As this island would have been a logical port of call for travelers – and their wares – arriving from Korea and further afield, some have claimed that it is this Mishima that gives the pottery technique its name.

Meanwhile, owing to these contrasting theories, others argue that there is more than one Mishima ware. Or that the term has been applied to different schools of pottery at different times.

Despite this confusion, what is commonly referred to today as Mishima ware has a distinct style characterized by bold geometric lines on a pale biscuit-colored base. This effect is achieved not by painting, nor a novel firing method, but means of inlay; the potter etching a design into the surface of the bowl before filling the incisions with a darker-colored slip and removing the excess. It is a technique that originated in Korea, consequently some items that are today called Mishima ware are in fact Korean, not Japanese.

An Ōhi ware tea bowl in the Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Traditional Arts and Crafts, Kanazawa, Japan.

Although soemtimes considered a style of Japanese pottery in its own right, Ōhi ware is an off-shoot of Raku ware developed by the Ōhi family, who were themselves descendents of Raku III. Ōhiyaki usually takes the form of rough, high-sided cylindrical tea bowls, produced by the coil technique or hand-molded like Raku ware. See Raku ware for more information.

For Oribe ware see Mino ware.

A black Raku ware tea bowl.

Rustic and charming; perhaps superficially a little clumsy looking, but actually very sophisticated; for many people Raku ware is pretty much synonymous with Japanese pottery.

The kanji for Raku means “fun,” “pleasure,” or “enjoyment.” This is the name that was given to the inventor of Raku ware – a 16th Century tile-maker by the name of Chōjirō – by daimyo Hideyoshi. The name stuck. Both to the potter’s family and the style of pottery he created; delightful earthenware tea ceremony vessels that are hand-formed rather than thrown.

In many ways Raku ware is the simplest-looking of all Japanese pottery styles. Yet simultaneously it is perhaps the one that has the most character. Sometimes resembling obscure forest fungus, Rakuyaki is typically highly organic, and often quite quirky, in appearance.

The low firing-temperature used to make Raku ware means that it is usually quite porous; not ideal for liquid-holding vessels. Yet despite this, Raku ware invariably takes the form of chawan. And beyond the fact that Raku bowls are hand molded, it really is the low-temperature firing process that is key to the distinctive look of Raku ware.

Most Japanese pottery is slowly heated, and then allowed to cool naturally in the kiln over hours – or even days. In contrast, Rakuyaki is put into the kiln cold, and then once fired it is suddenly removed and left to cool in the open air. This shock treatment is responsible for many of the unusual and unrepeatable glaze effects of Raku ware.

As Raku-ware was first developed in Kyoto, technically it can be considered a form of Kyoyaki.

In the 1950s, the fast-to-heat, quick-to-cool firing techniques of Japanese Raku ware became popular in the United States and elsewhere. However, the methods employed and the results achieved by western Raku potters differ significantly from the traditional Japanese methods. As a result, many argue that the two should be considered separate disciplines.

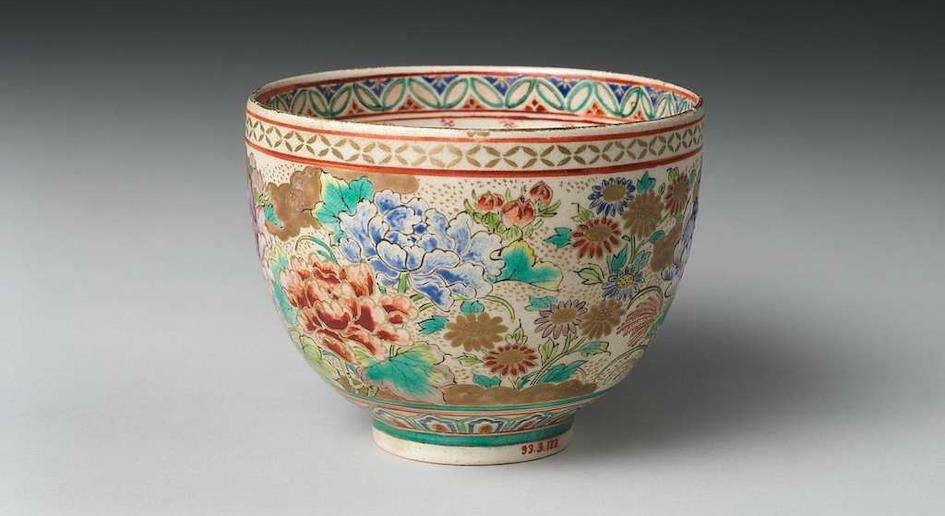

A Satsuma ware export tea bowl.

For many people outside of Japan, a satsuma is either a kind of citrus fruit or an historical rebellion involving disgruntled Samurai. It was once also the name of a Japanese province encompassing a large swathe of southern Kyushu island.

For most Japanese pottery enthusiasts, however, the word satsuma is synonymous with made-for-export enamel overglaze plates, bowls, and vases produced not only on Kyushu but in a number of Japanese regions – including Kyoto – from the 19th Century onwards.

Export Satsuma ware is one of the most distinctive and easily recognizable styles of Japanese pottery. It typically features an ivory-colored base, richly decorated with polychrome figurative motifs, and usually includes a lot of gold enamel.

This maximalist export Satsumayaki is not the only Satsuma ware in the game, though. And the original 17th Century Satsuma ware – i.e. pottery actually produced in the Satsuma region (modern-day Kagoshima) – was a lot more reserved in terms of embellishment.

Unlike the export ware, which was made specifically to cater to foreign tastes, early Satsuma ware was typically utilitarian in design, and either of a home-grown style or inspired by Chinese and Thai pottery. Early Satsumayaki often took the form of monochrome black (Kuro Satsuma) or white (Shiro Satsuma) pieces, or featured geometric designs (e.g. Sunkoroku; from the name of the Thai pottery, Sawankhalok, that inspired it).

Kyoyaki Seiji celadon wear from the 1800s.

Seiji ware is a form of celadon porcelain. Like all celadons, Seijiyaki is typically a delicate color somewhere between a pale blue and jade green; a byproduct of the reduction-fired iron-oxide glazing process. While the celadon technique originated in Northern Song dynasty China, and reached its pinnacle during the Southern Song dynasty, the technique also spread to other parts of Asia, including Japan.

Celadon production is tricky, with a high failure rate; meaning that many potters in Japan and elsewhere prefer to concentrate their efforts on more rewarding techniques. Nonetheless, production of Seiji celadon ware reached a high level in certain important Japanese pottery centers, such as Arita in Saga prefecture; a region blessed with large deposits of the kaolin-rich clay required for the production of porcelain greenware.

Bowls, cups, plates, and vases are all common Seiji ware items.

Many early Seto wares were attempts to recreate imported Ming pottery from the south of China. For more information about Japanese Seto ware, see Mino ware.

A drip-glaze Shigaraki storage jar.

Shigaraki ware has been produced for at least 600 years in the Shiga region east of Kyoto. As one of the older styles of Japanese pottery, it generally veers towards the more rustic and simple side of the spectrum. Traditional Shigarakiyaki typically takes the form of roughly textured water pots, sake bottles, flasks, jars, and other utilitarian items. Somewhat incongruously, however, the popular Tanuki good-luck figures found outside many Japanese restaurants are also classed as Shigaraki ware.

A Shigaraki climbing kiln.

Shigaraki ware is made from a distinctive type of warm-colored sandy clay extracted from the bed of Lake Biwa. While the forms of Shigaraki ware tend towards the simple and unadorned, they frequently lack the asymmetrical extremes of more wabi-sabi inspired Japanese pottery styles.

Nonetheless, there’s often a charming irregularity to the surfaces of Shigaraki ware, and fingerprints and other artifacts deriving from the throwing and firing processes are commonly seen on finished items. Shigaraki ware’s glazes, too, are rustic and unpretentious; typically mineral and ash glazes resulting from firing at a high temperature in hillside anagama “cave” or “climbing” kilns.

For Shino ware see Mino ware.

An 18th Century Takatori ware tea jar.

Takatori ware items are characterized by their simple, lightweight, and elegant forms; their contrasting and often dripping glazes; and deep earthy shades. Certain kilns producing Takatoriyaki today have been in continuous existence since the 17th Century when Takatori ware was first developed by a kiln at the foot of Mount Takatori in the Chikuzen region of what is now Fukuoka prefecture.

Owing to multiple glazing techniques and the use of unpredictable natural materials, Takatoriyaki frequently displays an unusual richness of color with soft gradations between tones. While technically Takatoriyaki is a stoneware ceramic (as defined by western tradition), a Takatori ware bowl is said to “sing” like porcelain when tapped owing to the thinness of its sides and the exceptional density of the clay used to make it.

Despite the relatively refined and sophisticated nature of Takatori ware, it still retains a notable wabi (simplicity) sabi (beauty) aesthetic. Indeed, when compared with forms of pottery eminating from areas further south and west on Kyushu island – such as Kagoshima and Arita respectively – Takatoriyaki sits very firmly on the rustic and random side of the Japanese pottery spectrum.

A Takatori ware festival has been held annually for the last 60 or so years in Nagota, a mountainous region between Fukuoka and Kitakyushu cities. Here you can purchase Takatori ware directly from producers at a significant discount over retail prices.

A Tamba ware sake bottle, early Edo period, 17th Century.

Variously spelled Tamba ware or Tanba ware in English, and called Tamba-tachikuiyaki in Japanese, this form of pottery developed in the Hyogo region of Kansai roughly 800 years ago. It is considered one of the prestigious “Six Ancient Kilns” of Japan.

Tamba ware can be typified as simple, no-nonsense, and organic-looking vessels for daily use. These often include jugs, mortars, storage jars; water pots; sake flasks, bottles, and cups; plus various tea utensils such as containers and bowls.

Tamba ware jars and bowls typically have a solid and pleasingly-balanced shape. They are invariably glazed in deep and earthy shades of black, brown, and – less frequently – beige (a style that is known as Shirotamba). Liquid Tamba ware glazes are often dripped, speckled, or splattered in application. Others are simply a reaction between the ash of pine wood used to fire the kilns and ores that are naturally present in the clay. Despite the limited tonal palette and techniques, there is considerable diversity within the Tambayaki genre.

Today Tamba ware pottery is available from a great many regional kilns. A popular Tamba ware festival is held in Tachikui Pottery Village every year with works from over 50 contemporary kilns on display.

Enjoyed the second part of our A to Z to Japanese pottery? Check out Part 1 here!