A ceramic plate from the Edo period.

A Potted History of Japanese Ceramics

Sacrificial Ceramics

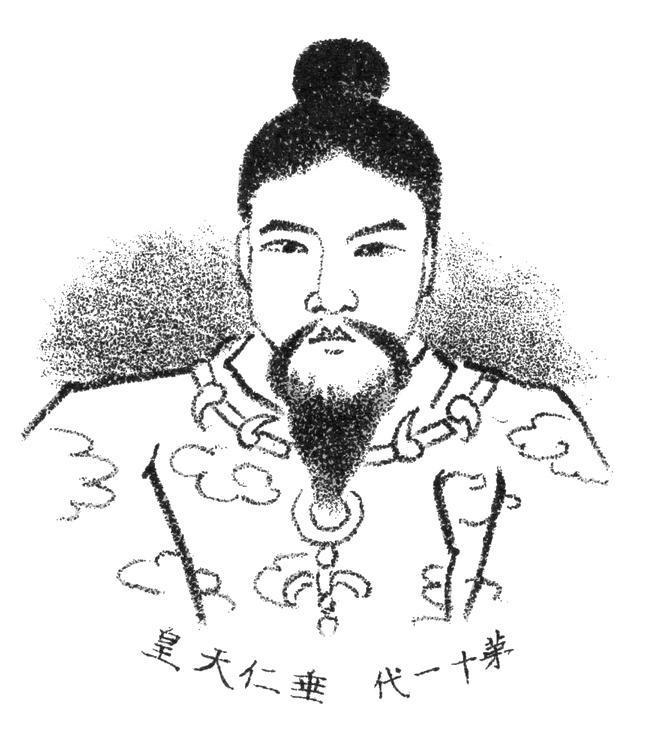

Legendary Emperor Suinin.

Japanese pottery has long held an important place in the nation’s consciousness. There’s a famous story that’s often told about how pottery stand-ins came to replace the tradition of human sacrifice upon the death of an emperor. Previously, when an emperor died, his retainers, horses, and other animals were buried alive along with him. A practice that was known as junshi – or “following in death”. But when the wife of legendary Emperor Suinin died, it’s said that he commissioned potters to create ceramic figurines of his wife’s retainers and animals, and had these buried instead.

In this way, the story goes, Japanese pottery was elevated to its current revered status.

Neolithic Origins

A spouted vessel dating from the Jōmon period.

Although it appears that the islands of the Japanese archipelago have always produced pottery in some form or another – items have been found dating back to Neolithic times – many of the initial innovations in Japanese pottery came about due to influence from either Korea or China.

As an example, early Japanese pottery was mostly quite simple in nature: during the Jōmon Neolithic period, pots were exclusively made by means of the basic coil method. But by Yayoi times (4th-3rd centuries BC), Japanese pottery had advanced considerably; local kilns evidently having learned about the potter’s wheel from China.

China and Korea’s importance to the development of Japan has been fairly constant over the centuries. Settlers from mainland China arrived on the southern Island of Kyushu, bringing with them influences that have strongly shaped what we now think of as Japanese culture in general; the nation’s customs, arts, cuisine etc. And today Kyushu remains an important center of Japanese pottery.

During the 8th Century, Tang Dynasty scholars from China were highly regarded in Japan, and their influence at the court of Nara, and later Kyoto, led to the development of new forms of Japanese pottery. This region, too, was to become one of the most prolific, and expert, in terms of Japanese pottery-making.

Knowledge Held Hostage

Daimyo Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

Although earlier exchange of knowledge took place in a context of learned civility and mutual appreciation, by the time of China’s Ming Dynasty, Japan was on less friendly terms with its neighbors.

Nonetheless, conquering campaigns into Korea by samurai warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi also resulted in the acquisition of new knowledge about pottery – whether Korea liked it or not – when his army brought back a great many Korean potters as prisoners of war. These potters established kilns in the fiefdoms of Hideyoshii’s feudal daimyo, and many of the techniques and innovations they imparted formed the basis of Japanese pottery as we know it today.

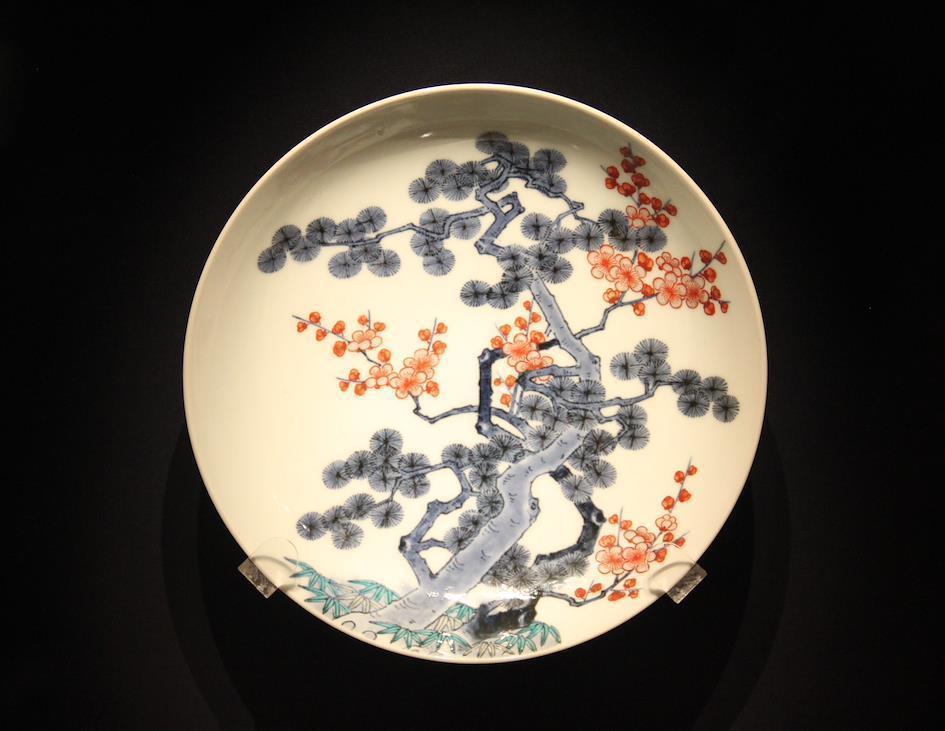

An Edo period porcelain plate.

Perhaps the most significant of these leaps forward was when one Korean potter discovered that there was silica-rich clay suitable for the creation of fine porcelain on the island of Kyushu.

While porcelain had long been coveted in Japan, it had hitherto only been known to the Japanese as an imported luxury, and the technique itself had stubbornly eluded local potters. By the mid 19th Century, however, porcelain production had become widespread throughout the archipelago and porcelain objects were part of the daily lives of most Japanese people.

The Tao of Tea

The chadō as seen in a woodblock print by the artist Toyohara Chikanobu.

As we’ve seen, the early development of Japanese pottery owes a great deal to the influence of other East Asian cultures. And while the tale about Emperor Suinin is likely just a myth, it certainly illustrates the elevated position that pottery occupies in Japanese culture.

Yet arguably the primary reason why Japanese pottery enjoys the degree of prestige that it does today is because of something else entirely; tea. Although most frequently translated into English as a “tea ceremony,” the Japanese term chadō actually implies much more than a simple ceremony. It is almost a way of life – based around tea drinking.

Of course, tea itself was first imported to Japan from – you guessed it – China. But by fusing the practice of tea drinking with Shinto and Zen Buddhist thought. the Japanese – particularly under the patronage of the daimyo – elevated the chadō to a philosophical and spiritual practice.

An 18th Century Japanese tea bowl.

Perhaps even more significant, at least in terms of establishing the importance of pottery in Japan, is that once samurai became involved, the chadō also became highly politicized. Of course, the chadō requires chawan (tea bowls). And so the more important tea became to Japanese culture, the more important pottery became, too. Indeed, warlords were often rewarded for their military successes with priceless ceramic tea utensils. In this way Japanese pottery was inextricably linked with prestige and power.

Industrial Dilution

By the 1930s Japan was a fully industrialized nation.

Up until now Japan’s relationship with pottery had largely been artisinal. True, alongside elegant tea ceremony items there had always been potters making more utilitarian vessels and tableware. Meanwhile export porcelain from Satsuma and Arita was produced on a large scale; but these items were not intended for local consumption.

Yet all this was before growing influence from further afield – specifically Europe and the United States – made mass production processes seem highly appealing. Necessary even.

Equally important, though, was the transition of the Japanese political system from feudal back to imperial. No longer could peasant potters rely upon the patronage of local feudal lords for their livelihoods. Meanwhile the public demanded more porcelain wares, and a great many factories now sprung up to provide them.

The result being that, by the end of the 19th Century, most pottery in Japan was of a distinctly industrial nature.

A Return to Form

Tokyo’s Nihon Mingeikan Museum

The upshot of all this is that Japanese folk pottery was virtually extinct by the time that Sōetsu Yanagi’s homegrown Mingei movement began to herald the unknown craftsman in the 1920s. And in many ways Mingei can be looked upon as a nationalist revival in the face of acute foreign threat.

Since that time, though, there has been a resurgence of interest in traditional Japanese pottery techniques and forms. And today it’s common to encounter beautiful handmade pottery in galleries, craft fairs, weekend markets, and even department stores all across Japan.

Of course, as with any other country in the world today, most Japanese people have neither the inclination nor the income to fill their homes with exquisite handmade ceramics. The average citizen eats their meals off mass-produced dishes from big box stores like Ikea and Muji, not hand-thrown rustic masterpieces.

Contemporary Japanese pottery on show at a craft festival in Kyoto.

(photo ©Christian Kaden www.Japan-Kyoto.de)

Nonetheless, the appreciation of pottery remains high among Japan’s population in general. And many people with regular day jobs spend a portion of their free time engaged in pottery.

Meanwhile, most full-time Japanese potters probably don’t expect their practice to make them rich any time soon. Indeed, for most people in Japan pottery remains an art rather than an industry; with all the economic challenges that being an artist – anywhere in the world – typically involves.

Despite this, clusters of single-artisan and small-to-mid-size kilns can be found in many regions of Japan today; particularly in rural areas and small towns with a long history of producing pottery. While the tradition of apprenticeships continues in many historical pottery centers, modern apprentices are as likely to be city-born implants – or even foreign-born disciples – as they are to be the direct descendants of local masters.

The Unique Character of Japanese Pottery

As is invariably the way with Japanese artists and artisans, Japanese potters carefully studied, emulated, mastered, and finally improved upon the techniques they learned from China and Korea. Along the way, they also made more than their own fair share of innovations and discoveries for themselves.

So while Japanese pottery owes a considerable debt to the traditions of neighboring countries, over the centuries it has developed a unique and highly distinctive character of its own. In fact, in terms of contemporary ceramic practice at least, today pottery is perhaps associated with Japan more than any other country.

A fashionably minimalist cafe in Tokyo

(Photo John Gillespie via Wikimedia Commons)

There is a certain minimal and subdued aesthetic – favored by hip coffee shops the world over – that is often thought of as uniquely Japanese. There’s little doubt that Japanese pottery has played some part in establishing this idea of Japan as a paradise of wabi-sabi simplicity and the quiet contemplation of natural beauty and imperfection.

But the fact is, for every Marie Kondo-style militant minimalist, somewhere in Japan there is also a mega-hoarder living in a “gomi-mansion” with trash piled from floor to ceiling. And for every peaceful Zen garden, there are probably a million aging and patched up homes featuring exteriors cluttered with rusted metal siding, dilapidated aircon units, laundry racks, a spaghetti of electrical wires, and assorted other unsightly debris.

In short, there’s more than one Japan. And it’s the same for Japanese pottery; contrasting styles and approaches exist within the nation’s ceramic output.

However, the comparison of Zen aesthetics with ramshackle suburban shacks is not meant to imply that one particular style of Japanese pottery is inherently superior to the other, but simply to say that the umbrella term “Japanese pottery” actually encompasses a diverse range of philosophies, methods, and results.

Still, we can broadly say that most Japanese pottery falls into one of two main – and quite opposing – categories: the random, and the controlled. Keep in mind that these are intended as somewhat loose terms. And some styles of Japanese pottery cannot be so cleanly placed in either one camp or the other. Nonetheless, we can define these two dominant styles as follows:

A Raku ware tea bowl.

As the name suggests, there is an element of arbitrariness to this kind of Japanese pottery. The potter allows – even encourages – the process to dictate the outcome to some degree. Here shapes are simple; execution is rustic: embellishment is either quite minimal or raw in application; a feature is often made of the natural colors of the materials; and, perhaps most importantly, defects and errors resulting from the processes of throwing, glazing, or firing the pots are embraced as enhancing the beauty of the object.

In short, while an individual potter obviously has a considerable degree of creative control, the final result here is as much due to the “will” of the methods and materials themselves as it is to the deliberate designs of the maker. Although rustic pottery has always existed in China, Korea, and elsewhere, nowhere was it so highly valued as in Japan. In this way it became something uniquely Japanese.

A Nabeshima ware dish.

With this kind of Japanese pottery, on the other hand, nothing is left to chance. The philosophy is one of absolute control and perfection; mastery over both the materials and the methods used. Here it’s much less likely that any natural clay will be left visible on the finished item. All-over glazes and enameling are the norm. Decoration is often rich and complex, requiring multiple, intricate steps to complete. The maker doesn’t “listen” to the clay, but shows it exactly who is boss.

Many of the advanced techniques employed by Japanese potters were of course originally learned from China and Korea. But as is so often the case, once Japanese potters acquired these techniques, they made it their business to achieve total mastery over them.

Conclusion

Japanese pottery has a long and illustrious history. And while the influence of China, Korea and – to a lesser extent – other Asian nations is undeniable, Japanese potters have clearly made the discipline their own.

Of course, today Japan is one of the most technologically advanced and industrialized nations in the world – having long ago shifted to mass-production methods. Yet small-scale artisinal pottery is still alive and well in the country in the form of thousands of local kilns. This means that for craft and pottery enthusiasts, Japan is an absolutely fantastic place to visit.

Keen to learn more about Japanese ceramics? Check out our A-Z Guide to all the different Japanese pottery styles here.